Recording the past in the words of those who lived it

"I fear I have failed in my effort to understand her, but at least I tried — sometimes, that's all one can do," wrote Rao Chenxi, a student at Beijing's Moonshot Academy, a private institution serving students from primary through high school. Her words appear in the epilogue she appended to her oral history transcription, a project centered on her paternal grandmother — a woman toward whom she had long harbored deep misgivings.

"Why does oral history matter? Because beyond restoring marginalized voices and fleshing out the bare bones of major historical events, it has the power to bridge generations and, at times, to heal old wounds. And even when reconciliation proves elusive — as in my student's case — the process still fosters personal growth," says Guo Xuzheng, the teacher who launched the family oral history project at his school in 2023, a program that has since drawn participation from more than 60 students, including Rao.

"Most students chose to interview their parents or grandparents, and many were astonished by what they uncovered: a grandmother who had married twice; a mother they had always seen as gentle and unassuming who, in her youth, had been a rock 'n' roll 'cool girl' — sides of their elders they had never imagined," Guo says.

The discovery of a life that existed before someone became a parent or grandparent, he adds, often reshapes how the younger generation perceives them. Some children later reflected that learning how earlier generations weathered hardships helped them confront their own setbacks, passing down a quiet form of resilience.

"Many of them initially thought that listening to their elders' stories would be dull. But as they continued, they found that simply offering older family members the chance to speak — and letting them feel truly heard — carried unexpected emotional weight," says Guo, 30.

Guo is currently developing an online platform to host all the recordings from his project, taking inspiration from IWitness, an educational archive of survivor testimonies hosted by the Shoah Foundation at the University of Southern California. Beyond offering thousands of video accounts from the Holocaust and other genocides, the foundation has also pioneered Dimensions in Testimony, which uses advanced video and AI technology to create interactive "virtual conversations", enabling users to ask questions and receive real-time responses from prerecorded testimonies.

One of the figures featured in the archive is Xia Shuqin, a survivor of the six-week Nanjing Massacre — the campaign of killing and devastation carried out by invading Japanese troops between December 1937 and January 1938, which claimed an estimated 300,000 lives. She is the only interviewee who speaks in Chinese.

On the screen, she sits in a red chair, with a dialog box beside her where users can type or speak their questions. When asked, "What happened on the day the Japanese soldiers came?", the digital Xia begins her account. One can hear the tremor in her voice as she raises her hand above her head, speaking Mandarin tinged with a local accent: "Both of my in-laws were killed right down here. Their heads were blasted open — brains everywhere."

Guo says that the Shoah Foundation's work demonstrates the possibilities that AI brings to the field of oral history, allowing it to reach and feel relevant to a much broader and younger audience.

Lin Hui, executive director of the Center for Oral History at Beijing's Communication University of China, agrees. "AI has the potential to revolutionize oral history. It can link archives across the world, creating instant connections among vast collections of material. When it highlights shared details mentioned by people who never knew of one another's existence, it helps us connect the dots and bring to light discoveries that might have remained out of reach," she says.

At the start of each semester, before students begin collecting oral histories from their families, Guo insists they study the past. "Every individual's story unfolds within the context of their era, and for that reason, anyone doing oral history must first be a student of history," he says.

A similar conviction drives the work of Qi Lixia, founder of the Mulan Community Service Center in Beijing, a public welfare organization founded in 2010 to support migrant women workers in Beijing.

"Leaving their homes and often their children behind, these women work in a city that largely treats them as outsiders. They are the footnotes of our era," says Qi, 52. Once a primary school teacher who became a migrant worker herself, standing at suitcase assembly lines in a factory in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, Guangdong province, Qi has collected more than 60 oral testimonies from women she has met through her work at the service center over the past 14 years.

"China's vast migrant-worker population began to take shape in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as the country shifted toward a market economy. It is unmistakably a product of its time. When China has long moved beyond this chapter, perhaps a century from now, I hope people will look at these records and recognize that these lives were lived in full color, not lost to the anonymity of numbers," says Qi, who sees oral history work as a natural extension of her community efforts, which focus on providing educational and recreational support to female migrant workers and their children.

"Oral history carries an inherent humanitarian dimension — simply knowing that someone cares enough to listen can be deeply comforting and reassuring for many interviewees, especially those who never imagined anyone would take their stories seriously," says Qi. "After sitting down with a 'sister' for several hours, you see a mix of joy and sorrow — pain rising as old wounds are revisited, yet relief and even a quiet happiness in finally having her story heard."

According to Qi, she once enlisted university student volunteers to help collect the stories, but the results were less than ideal. "Our 'sisters' struggled to relax and open up, feeling little connection with their interviewers."

Reflecting on the craft of gathering the stories, Lin says, "Oral history takes shape through listening. A listener must convince the interviewee that they stand on an equal footing — and that can only happen if the listener truly believes it.

"Oral history bridges personal memory with public record, transforming lived experience into historical evidence. At its core is the democratization of how history is made," she adds.

For the past few months, Guo has sat down with his 88-year-old maternal grandmother to record her story — without ever once using the term "oral history". "Of my four grandparents, she is the only one still alive. Despite the onset of Alzheimer's disease, she remembers her youth with striking clarity," he says.

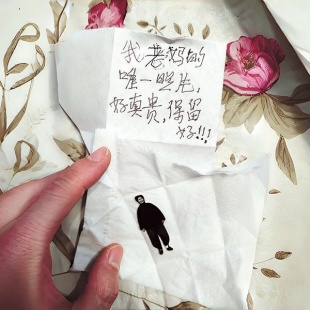

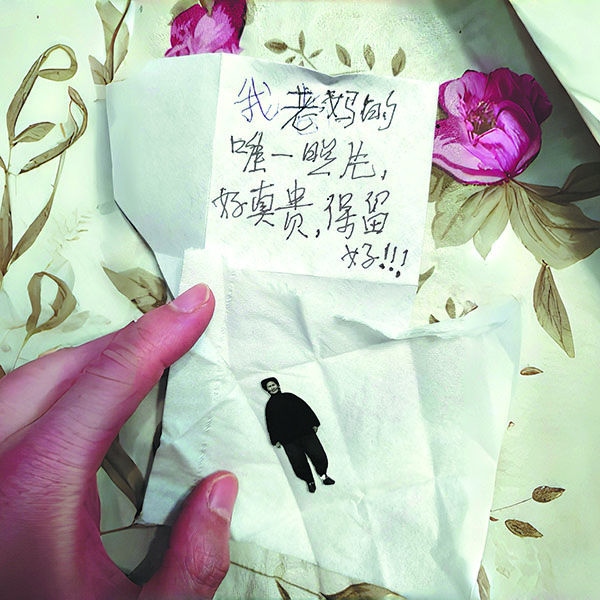

Guo says his oral history project would never have existed without his grandmother who, without knowing it, made him acutely aware of the weight of family history. "One day, in 2022, while visiting her, I happened to open a drawer where she kept odds and ends. Inside was a carefully folded paper packet," he recalls.

Peeling back the outer sheet, he discovered a second layer of neatly folded tissue. Inside was a tiny black-and-white photograph, scarcely two finger joints long. There was no background — only the cutout figure of a woman, slightly older, wearing a hat, her feet bound, her eyes looking straight into the camera, a faint smile on her face.

Scrawled across the tissue, in his grandmother's handwriting, were the words: "My mother's only photograph. So precious. Keep it well!"